Mental Effects on Physical Health: The Mind-Body Connection

Conventional Western human and veterinary medicine still bear the legacy of French philosopher Rene’ Descartes (1970), who promoted the false dualism of the mind being separate from the body, and the belief that animals were unfeeling machines. Such mechanomorphization of non-human animals became the scientific consensus that condemned the belief and empirical evidence of emotional states in animals as sentimentally misguided anthropomorphism. In spite of Charles Darwin’s work (notably his book The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals), and other scientists’ and philosophers’ opposition to Cartesian dualism and mechanistic reductionism, the resistance to accepting that animals have minds and emotions endured for over three hundred years since Descartes, especially in scientific, biomedical, and related circles of animal use and abuse, in part because of even deeper religious and cultural attitudes toward non-human life (Fox 1996). As late as the 1960s skepticism was expressed by some veterinarians over empirical evidence that dogs will feign injury to a limb in order to seek attention (Fox 1962). Some members of the profession scoffed at such evidence, contending that they would be called on to be pet shrinks or behavioral therapists, while others acknowledged the need for more expertise and research in normal and abnormal behavior in animals.

The mind-body/psyche-soma dichotomization greatly limited progress in human, veterinary, and comparative medicine, and contributed to much animal cruelty and suffering. This was compounded by specialization that led to the ‘fragmentation’ of seeing and treating the animal and human patient as a whole being, and of the conceptualization of health and disease processes. Another product of dualism and reductionism was the dichotomization of the essential organism-environment unity that tended to preclude the consideration and recognition of social and environmental influences on mind and body; i.e., on the animals’ emotional and physical well-being.

Ethos, Ecos and Telos

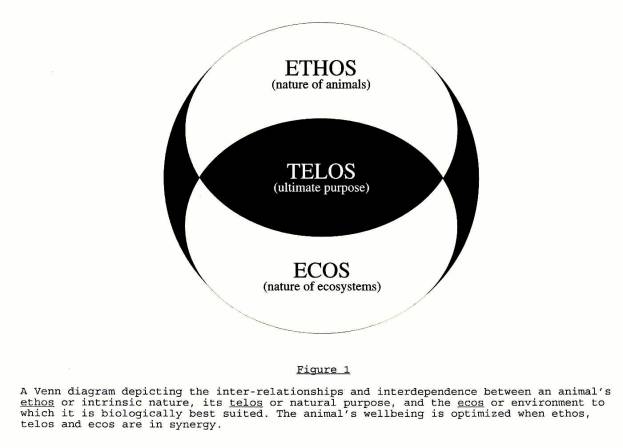

Animal health depends upon animal well-being, the bioethical and scientific parameters and indices of which include provision of an environment (the ecos) that is optimal for animals’ basic physical, behavioral, and psychological requirements (their ethos, or spirits), and which maximizes animals’ telos, their natural, ecological purpose and biological value and role (Fox 2001). Human imposed and directed influences on animals’ ecos include housing/husbandry conditions and standards of care and environmental quality; on animals’ telos include economic, cultural and other human values and interests; and on animals’ ethos, as affected by selective breeding, genetic engineering as well as early handling and socialization, or lack thereof. (See Fig.1)

These three spheres of animal life, ethos, ecos and telos translate into the mind-body-organism-environment interfaces that provide a more holistic paradigm for addressing animal health and welfare concerns (Fox 1997).

Since the mind is in the body, the body is in the mind. Likewise, since the elephant is in the forest and the forest is in the elephant, how can we put elephants in chains and force them to help people destroy the last of their forests, or put them in circuses and zoos and expect them to be healthy and reproduce and not go berserk? Elephants and other animals wild and domesticated under our dominion surely need not have to be victims of such mind-body-environment dislocations that result in suffering and distress.

Only in the last fifty years have scientists, bioethicists, and veterinarians begun to consider the stress, distress, and suffering of animals under conditions of extreme and chronic confinement and environmental deprivation, often coupled with inconceivably high stocking densities (as with the intensive production of farmed animals). Such mistreatment creates pathogenic conditions, especially as a result of stress and immunosuppression, for the proliferation of infectious and contagious ‘domestogenic’ and production-related diseases (Fox 1984 & 1986). These animal health and welfare problems are significant economic and public health concerns that will not be rectified by new vaccines, stronger antibiotics, and other drugs that are not all environmentally-friendly and consumer-safe. Neither can the answer lie in selectively breeding and genetically engineering animals for the food, fiber, and biomedical purposes; nor is it to be found in the pet industries designed to enhance the animals’ utility, productivity, and adaptability.

This is because there are biological limitations that should translate into ethical limitations in how we should alter the ethos and ecos of animals for our own pecuniary and other purely human ends (Fox 1992 & 1999).

Before reviewing some landmark studies, old and new, of the mind-body connection and the influence of emotional and cognitive states and environmental influences on animals’ health and well-being, I wish to summarize the above overview of principles of optimal animal care. The following five bioethical principles combine to make a simple formula to help ensure animals’ health and well-being: Right Environment + Right Genetics/Breeding + Right Understanding + Right Relationship + Right Nutrition = Animal Health and Well-being.

Applying these principles within the holistic paradigm that addresses the animals’ ethos, ecos, and telos facilitates the objective determination of animal health (which is not simply the absence of disease); the assessment of stress and distress using established physiological, neurochemical, and behavioral indices; and identification of welfare parameters and basic standards of animal husbandry that meet animals’ physical requirements and psychological/behavioral needs.

Steps Toward Understanding

Significant advances have been made in the science of applied animal ethology and welfare assessment and improvement since the first English language book on this interdisciplinary subject was published in 1968 that I edited and entitled Abnormal Behavior in Animals. This book included essays by veterinarians, ethologists, neuropsychologists, clinical and experimental psychologists, and Pavlovian physiologists. One chapter by L. Chertok entitled Animal Hypnosis (an intriguing mind-body phenomenon in vertebrate and invertebrate animals) was reprinted from the first book ever published, to my knowledge, in 1964 that addressed animals’ emotional states, and behavioral (psychogenic) and psychosomatic diseases associated with stress and distress, from a primarily veterinary perspective. This book, edited by two French veterinarians, was called Psychiatrie Animale, (Brion & Ey 1964).

Between the 1960s and 1980s there was increasing interest in comparative psychiatry from Harlow’s maternally-deprived caged macaques to other experimental psychologists’ often gruesome studies of learned helplessness in rats repeatedly half-drowned, and studies of restrained dogs being given inescapable shock (Overmeier 1981), the end product being a proposed model of human coping in the presence of hopelessness and depression, that might be of value in testing the new anti-depressant psychotropic drugs that were being developed around that time, (see also Seligman 1975).

Disturbing, but not devoid of some value in awakening our understanding of the similarities in how humans and laboratory animals manifest distress and psychological suffering, these experiments should never be, nor need be ever repeated. Nor should those of Pavlovian, classical conditioning, that resulted in much animal suffering, especially of dogs; yet like the Nazi medical experiments on concentration-camp prisoners, these experiments provided empirical evidence affirming the mind-body connections of stress and distress, as well as various psychogenic, psychosomatic, traumatic, and infectious disease processes (Pavlov 1928, Gantt 1944, Lidell 1956).

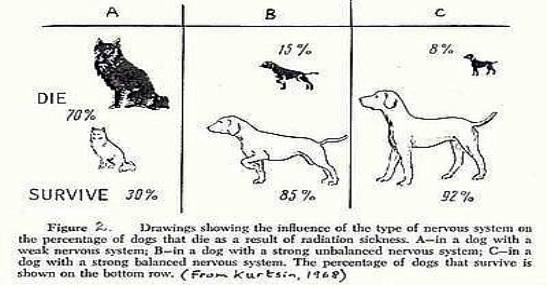

Using Pavlovian conditioning, researchers were able to identify and characterize different animal (dog) temperaments, and went on to demonstrate how these various psychomorphs responded to pain, conditioned fear (anxiety, terror), infections, trauma (like having a leg broken), and total body radiation (see Fig, 2), the details of which were provided by Prof. I.T. Kurtsin which I published (along with a review of Harlow’s infant monkey maternal deprivation research by Gene Sackett) in Abnormal Behavior in Animals.

Domestication Effect

The seminal and less invasive research findings of another Soviet scientist, Prof. D.K. Belyaev, were first published in the West in another book that I edited entitled The Wild Canids: Their Systematic Behavioral Ecology and Evolution. Belyaev and Trut (1975), reported changes in reproductive activity that they regarded as a ‘destabilization’ process in captive silver foxes after several generations of selectively breeding the most tractable and docile. Thereafter, generations of foxes developed floppy ears and piebald coats, females became bi-estrus rather than having one heat per year. Belyaev and Trut showed how the domestication process (of selectively breeding the most docile) affected animals’ morphology and physiology, notably reactivity to ACTH injections and to psychological stress. American researcher Curt Richter came to similar conclusions in his earlier (1954) review research on the effects of domestication on the Norway rat, concluding that the laboratory rats were relatively hypergonadal and hypoadrenal compared to their wild counterparts, such endocrine changes being attributed to artificial selection for high fertility and docility. Domestication, according to Belyaev and Trut, influences the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal-gonadal systems, the selection from docile, tractable behavior leads to the dramatic emergence of new forms (phenotypes) and to the destabilization of ontogenesis manifested by the breakdown of correlated systems (adrenal-pituitary, gonadal-pituitary), created originally under stabilizing (i.e., natural) selection. (For some of the earliest original thinking and research in this area, see Stockard 1941).

Experimental psychologist E. Gellhorn (1968) (who made cats more docile by eliminating their senses of smell, sight and hearing to make them more trophotropic or parasympathetic system dominant-they slept more) was coming to conclusions similar to those of Belyaev and Trut, but by a less ethical/humane path, that he felt had implications for neuropsychiatry. The tuning of the parasympathetic and adrenergic systems, the latter being linked with the neurohypophysis/pituitary-gonadal and other neuroendocrine and immune-system modulating mind-body connections, became the focus of converging and diverging animal studies during this time that helped further our understanding of the mind-body and environment connections, and effects of domestication.

Robert Ader, in 1981, put several authors together in a book that supported his thesis that mental states (emotions), distress, and stress affect the body, especially the immune system. It was appropriately titled Psychoneuro-immunology.

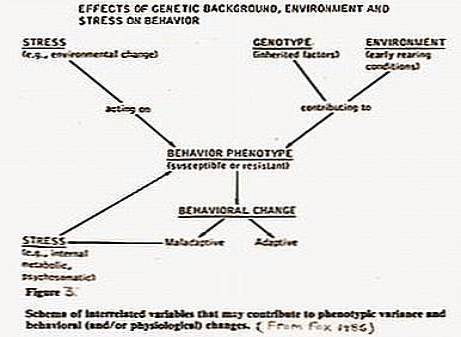

This was a major turning point in demonstrating how social, emotional, and environmental stimuli/events/experiences can influence animals’ neuroendocrine system, stress tolerance, and disease susceptibility. This new understanding demanded a more holistic approach in veterinary practice to the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of domestogenic diseases and syndromes in farmed, laboratory, zoo, and companion animals. A holistic approach to animal health and welfare in the biomedical and intensive factory farm environments was particularly important for scientific and financial reasons, as well as on moral grounds (Fox 1984 & 1986). The holistic, interdisciplinary approach to addressing mind-body-environment dislocations (see Fig. 3) that may cause animals to suffer and become dis-eased, called for applying ethology, the study of animal behavior, to the science and act of veterinary medicine and comparative medicine which I stressed in the Wesley W. Spink Lectures on Comparative Medicine at the University of Minnesota, (Fox 1974).

The British Veterinary Ethology Society, of which I was a founding member, was established around this time and after only a few years became the International Society of Applied Ethology, encouraging veterinary colleges and animal science departments to offer courses and conduct research on this subject. Since these encouraging beginnings several benchmark studies, symposia, and texts have been published, (Katcher and Beck 1983, Lawrence and Rushen 1993, Davis and Balfour 1992, Panksepp 1998, Dodman and Shuster 1998, Moberg and Mench 2000).

A more holistic understanding of animals’ ethos and welfare requirements has also come from research in cognitive ethology, the field of study that investigates animals’ consciousness, mental states, and the umvelt or animals’ perceptual world (Griffin 1997, Bekoff 2003).

The British Brambell (1965) report on farm animal welfare included the following statement by eminent neurologist Lord Brain:

I personally can see no reason for conceding mind to my fellow men and denying it to animals. Mental functions, rightly viewed, are but servants of the impulses and emotions by which we live, and these, the springs of Life, are surely diencephalic in their neurological location. Since the diencephalon is well developed in animals and birds, I at least cannot doubt that the interests and activities of animals are correlated with awareness and feelings in the same way as my own, and which may be, for ought I know, just as vivid. McMillan (2003) has stressed the clinical and animal welfare importance of considering more than physical pain and relief of same, since “emotional pain”, (as fear, panic, anxiety, helplessness and depression), are welfare-related concerns in addition to physical pain per se.

Developmental Effects

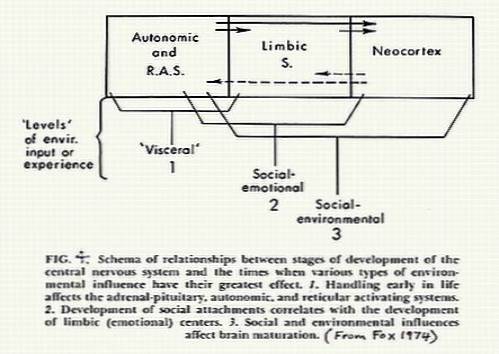

Further understanding of developmental processes that influence the behavioral phenotype come from studies of early experiences both pre- and post-natally (see Fig. 4) that entailed various handling procedures of pregnant animals, mainly mice, and of the offspring soon after birth. Gentle handling on a regular basis was found to affect emotional reactivity, learning ability, stress resistance, and disease susceptibility that had profound implications in animal husbandry and which pointed to an epigenetic, neo-Lamarkian phenomenon of inherited, intergenerational environmental influences on animals’ physiology and behavior (Levine and Mullins 1966, Denenberg 1967). As a consultant in Biosensor Research for the Walter Reed Army Medical Center in the early 1970s, I applied some of these findings in developing a socialization and rearing program that provided selected beneficial experiences to puppies during their formative weeks. This Superdog project that I made available to puppy owners and breeders in my 1972 book Understanding Your Dog was aimed at enhancing in-field performance, stress-tolerance, and disease resistance in adult German Shepherd dogs under combat conditions in Vietnam.

This field of developmental psychobiology showed that genetic background/heredity, and pre- and early postnatal experiences influenced animals’ physiology, behavior, temperament, learning ability, and stress and disease resistance when early handling, socialization, and environmental enrichment were provided during critical or sensitive periods of development (Scott and Fuller 1965, Fox 1971, McMillan 1999b & 2002). Such profound consequences of external stimulation/experiences on the mind-body connection are now more widely recognized, providing a scientific basis for the value of tender loving care (TLC). Spitz (1949) first pointed how the lack of TLC can cause marasmus, growth retardation, increased morbidity, and mortality in orphaned, institutionalized human infants. The relevance of these findings to improving the husbandry, health, and productivity of farmed animals was realized in particular by Hemsworth and Coleman (1998), who went on to demonstrate that sows that had been gently handled and socialized early in life had more offspring than sows not given such early experiences.

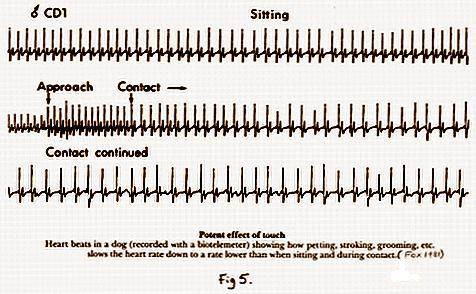

The attitude of animal caretakers toward the animals under their care is significantly influenced by the conditions under which they work and the conditions under which the animals are kept (Seabrook 1984), which underscores yet another variable in assessing animals’ welfare and in setting optimal husbandry standards for various animal species. An animal caretaker’s gentle handling can affect heart rate and other physiological indices (see Fig. 5). The petting of rabbits can significantly mitigate the harmful effects of a high fat and cholesterol diet, reducing the incidence of artherosclerosis by some 60 percent compared to non-handled rabbits fed the same diet, (Nerem et al 1980). This research further underscores the importance of recognizing the interactive nature of animals’ social environment, emotional state, nutrition and health.

The research of veterinarian W.B. Gross, now Prof. Emeritus, Virginia and Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine, has shown the complexities of genotype-environment interactions on the development, behavior, stress resistance, and disease susceptibility in poultry, the clinical and husbandry implications of which are indeed profound. Dr. Gross prepared a synopsis of his interdisciplinary research from the perspective of the mind-body connection in poultry for inclusion in this review that is appended at the end of this chapter. He has also shown the benefits of vitamin C (4 mgm/kg time-release granules) that blocks the adrenal stress response in the clinical setting of dogs presented with various forms of cancer, with promising results, (Gross et al 2001). These findings indirectly support the claimed clinical benefits of corticosteroid replacement therapy for a variety of chronic degenerative diseases in companion animals documented in practice by Pletchner (2003). As with Gross’ different lines of poultry, different breeds of dogs, cats, pigs, cattle and other domesticated animals and hybrids thereof, with different temperaments/emotional reactivity, respond differently to stress and other social and environmental stimuli, which can mean different disease profiles in animals raised under similar conditions. “Fitness”/adaptation under natural conditions calls for a set of organismic responses that evolve over millennia. Animals under unnatural conditions of domesticity/captivity, to which they are not genetically and behaviorally pre-adapted, often mobilize maladaptive responses and being unable to adapt, suffer the consequences physically and psychologically.

Psychopharmacology

With the discovery of cholinergic, serotonergic, dopaminergic, and other neurochemical pathways and opioid, benzodiazepine, and other neural receptor sites that mediate and modulate various subjective, cognitive, and affective states, the field of behavioral psychopharmacology has opened a new door into the mind-body connections of human and non-human animals.

The mind-body connections of neuropeptides (like the opiates) centered in the limbic system (the ‘seat’ of the emotions) form a regulatory matrix of emotional, behavioral, and physiological processes that help promote animals’ survival and well-being. Neuropeptide receptors have also been found in lymphocytes and in spleen monocytes (that secrete ACTH and endorphin), creating a linkage with the immune system and central nervous system (CNS). Receptors for immunopeptides such as lymphokines, cytokines, and interleukins have been found in the CNS, and opiate and other receptors in the gastrointestinal tract and throughout most body organs and tissues. This means that there is bidirectional communication between mind and body, brain, and immune system such that mood/mental state is linked with cellular defense and repair mechanisms (for a review see McMillan1999a).

The health benefits of companion animals to their human guardians, and vice versa, are associated at this molecular level with beneficial changes in levels of neurochemicals such as endorphin, prolactin, oxytocin, dopamine, and phenylethylamine in both humans and dogs during friendly contact (Odendaal and Meintjes 2003). It is because of these mind-body linking neuropeptide and other chemical receptor systems that it is possible to lower an animal’s blood pressure and enhance their immune response through classical and operant conditioning, biofeedback, and simply by gentle regular petting. As Seligman (1975) has shown, control and predictability are important elements of coping in human and non-human animals for whom an environment in which they have little control or predictability leads to helplessness, depression, and immune-system impairment.

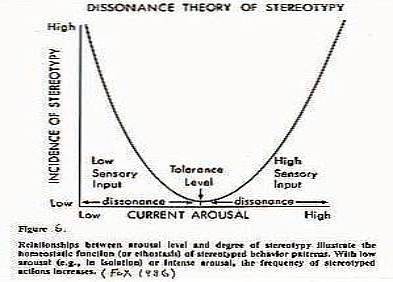

The thyroid gland can also be involved in stress/distress reactions; captive wild rabbits exposed to dogs, for example, may die from acute thyrotoxicosis (Kracht 1954). Loneliness and separation anxiety may be manifested as colitis-like diarrhea and bloody stools in dogs precisely because of these environment-mind-body connections, a greater understanding of which calls for the practice of holistic veterinary (and human) medicine. Stress-free understimulation, i.e. social isolation leading to boredom vices (Wemelsfelder 1990) and higher mortalities, can be as detrimental as overstimulation (as through overstocking). This means that there is an optimal level of stimulation and stress for individuals, breeds, and species called eustress that help maintain psychophysical homeostasis as distinct from distress (from too little or too much stimulation) that leads to dystasis, i.e. behavioral, metabolic, and cellular disruption of homeostatic systems.

The increasing spectrum of psychotropic drugs, analgesics, tranquilizers, anxiolytics, dissociatives, and skeletal muscle relaxants is of considerable value in veterinary practice as other contributors to this volume have documented. They are especially valuable in reducing stress and fear in wild animals needing veterinary attention, and in dealing with the obsessive-compulsive, and separation-anxiety afflicted companion animals. But they should never become a matter of routine prescription for animals suffering from emotional/behavioral/cognitive disorders to the exclusion of providing the right understanding, relationship, and environment, which are the best preventives of many behavioral anomalies, psychogenic disorders (like self-mutilation in bored and anxious captive parrots), and psychosomatic diseases (like ulcerative colitis in high-strung, i.e. highly empathic or extremely fearful German Shepherd dogs).

The cage stereotypies of animals in barren environments may be associated with developmental abnormalities in the brain and impaired basal ganglia activity (Garner & Mason 2002). As these authors conclude from their evidence for a neural substitute for cage stereotypy, stereotypic animals may experience novel forms of psychological distress, and that stereotypy might well represent a confound in many behavioral experiments. The effects of the impoverished laboratory cage environment and of environmental enrichment on brain development, neurochemistry, and behavior have been long recognized (Rosenzweig et al 1962, Diamond et al 1967). These effects can compromise both animals’ welfare and their utility for research (introducing uncontrolled experimental variables), as emphasized by Fox (1986), and more recently by Wurbel (2001). A new perspective on stereotypic behavior in horses has been given by Marsden (2002), who looks at various treatments from an ethological and animal welfare perspective, identifying those treatments that can be detrimental when the underlying motivation/frustration is not addressed. Stereotypic behavior can be interpreted as a maladaptive response to hypostimulation or hyperstimulation, (Fox 1986), the environmental dissonance between stimulus-input and the animal’s arousal level being homeostatically regulated by increased or decreased activity see Fig. 6). A bored, under-stimulated animal may groom excessively, sometimes to the point of self-mutilation, and behave similarly when stressed by fear or anxiety and frustration when confined, in a strange place, or in the presence of strangers. Such self-comforting behavior associated with hypostimulation and hyperstimulation can be correctly interpreted as obsessive compulsive behavior, but should be distinguished from schizoaffective disorder that can manifest similar symptomatology but have a different etiology and motivation. One example is the dog who self-mutilates after displaying agonistic behavior, the self-mutilation being a consequence of self-directed aggression, sometimes accompanied by psychogenic hallucinations, such as fly-snapping and staring at one spot.

The effects of living alone in a cage, pen, or room on millions of dogs, cats, birds, and other pets for long periods of time without human contact, and with all too often a complete lack of contact with another animal, is a veterinary medical and ethical problem. Reliance on psychotropic drugs to alleviate these adverse effects is neither an appropriate medical nor ethical solution.

Another group of chemicals influencing mind-body reactions that are generally much safer, if not cheaper than psychotropic drugs, are the pheromones, or animal essences, and the plant essences or essential oils derived from various herbs, flowers, trees, and other vegetative life forms whose phytochemical substances have co-evolved neurochemical affinities with the mammalian brain, neuroendocrine, and other systems, like the endogenous opioid beta-endorphin pain-alleviating receptor system that is present even in earthworms. Some of these essential oils may affect serotonergic, gamma-aminobutyric acid, and dopaminergic neurotransmission, or have anticholinergic, antispasmodic, and other effects on the mind-body that could prove beneficial to animals suffering from a variety of behavioral problems. Horses and other animals that develop stress- and boredom-related stereotypies and other obsessive-compulsive disorders develop elevated dopamine and opioid levels that may be inhibited by dopaminergic and opioid agonists. More research in the veterinary and animal husbandry applications of plant essences, popularly known as aromatherapy, is needed in this clinically promising but scientifically little understood area of alternative/complementary medicine (Bell 2002).

It might be rewarding to evaluate the euphoric, mood-elevating properties of essential oils like Bergamot and Clary Sage. After all, many cats enjoy mood-altering catnip. Clinical studies of a synthetic pheromone that contains chemical similar to those found in the sebaceous glands on the mammary region of nursing dogs have shown that the compound odor has a calming effect on many dogs suffering from separation-anxiety and fear of fireworks (Sheppard and Mills 2003).

Social Influences

Animal well-being includes happiness and playfulness which will take more direct human involvement, however, than magical oils and the offerings of behavioral pharmacology. I know farmers who play with their chickens, pigs, steers, cows, and ewes, like the Indian villagers who play and sleep with young goats and calves. These animals are healthier and more productive. Similarly, in families where there is no intra- or inter-species play provided for live-alone dogs, cats, parrots, and other pets, there are more health and behavioral problems than in families where the animals are happy because they can play (see Horwitz et al. 2002). Inter-species play, as between a billy goat and a young bull, a calf and two young dogs, a lamb and ten dogs, and a monkey with a pack of more than thirty dogs, a herd of twenty cattle and a band of more than ninety donkeys, that I have witnessed at IPAN’s Hillview Farm Animal Refuge, is a sight to behold. It is the essence of the joy of life that heals, makes whole, and inspires and affirms the will to be. Play is the best of all natural therapies; and it is a cardinal animal welfare science indicator of animal welfare and well-being.

The use of massage therapy and the Healing Touch (Fox 1997), can also be valuable in reducing animals’ tension, fear, and distrust, and help speed recovery from various conditions.

Pavlov’s demonstration that dogs can be conditioned to respond to injections of normal saline as though they had been injected with morphine raises the question of conditioned and associative learning and anticipation/expectation in relation to positive and negative placebo-like effects in animal patients. As McMillan (1999b) proposes, the goal of clinical application of placebo effects should not be to seek substitution of placebo treatments for standard treatments, but rather to use the placebo effects to accentuate the efficacy of such treatments.

Animals engage in mutual greeting displays and self-care and mutual-care behaviors, including grooming, making contentment sounds and various intention-movements or displays (like lip-smacking in macaques) of epimeletic (care-giving) and et-epimeletic (care-seeking) behavioral/motivational systems. Mimicking such care-giving behavior appropriate to the species is a prerequisite for veterinarians and animal handlers who need to enter an animal’s personal space and make physical contact. Giving a treat as a care-giving gesture is often the first step.

Some animals are highly motivated care-givers and as Chief Consultant/Veterinarian with India Project for Animals and Nature I have witnessed at our Hill View Farm Animal Refuge how the recovery of many frightened, sick, or injured animals is enhanced by the reassuring presence and attentions of our care-giving resident dogs, ponies, and cows. Being isolated from conspecifics, especially for sheep and for most young animals, can be extremely stressful. The staff are trained to feed animals treats and to groom or stroke them during various treatments like changing a dressing on a lacerated limb, be the animal a horse, half-wild bullock, or captive elephant. Epimeletic behavior and empathy make for good animal handlers. They also sleep with dogs, calves, baby elephants, and other animals, monitoring their condition, checking IV drips, etc., when emergency cases requiring intensive care come in for treatment. Most importantly, they are instructed to encourage the animals in recovery to play, engage with other healthy resident animals, and engage in natural behaviors in a free but safe environment rather than remain confined all the time in a small cage or pen.

Conclusions

I am glad of the opportunity to contribute to this important book that I see as a high watermark for the veterinary profession in helping accomplish what I have advocated my entire professional life: healing and enhancing the human/non-human animal bond through sound science, understanding, empathy, and respect. Then compassionate action will do less harm and a mutually enhancing human-animal bond can be established. My friend and mentor Thomas Berry (1999) put it this way: The universe is not a collection of objects, it is a community of subjects. Compassion will be absolute, or it is not at all.

The communion of subjects that I examine in my book The Boundless Circle creates what I call the empathosphere, a realm of empathic feeling that Sheldrake (2000), in his studies of dogs and cats who somehow seem to know when their human companions are coming home, calls the morphic field. It is a realm of in-feeling that, without further scientific study, will regrettably continue to be regarded as psychic or illusory to the rationally minded. Fortunately, some controlled experiments have demonstrated the beneficial effects of healing-directed prayer or distant/remote mental intentionality on such non-human subjects as bacteria, plants, chicks, gerbils, cats, and dogs (Dossey 2001, Grad 1964). These findings undermine scientism’s belief in consciousness as an epiphenomenon of brain neurochemistry, and support a holistic paradigm of consciousness as a fundamental principle that is irreducible to anything more basic, and which is both co-inherent and omnipresent, particular and universal.

Be this as it may, I urge all veterinary students as well as children and adults who have animals in their lives, to take time out, suspend all judgement and simply be with animals, ideally in situations where they have behavioral freedom and can be with their own kind. Observe them, feel with them/for them, and become them. Perhaps the animals may then welcome you to the empathosphere like many before you who became shamans, healers, good husbanders, and stewards of the land.

ADDENDUM

Mind-Body Connection: Lessons from Chickens

Mental perceptions of the environment are based on lifelong experiences and genetics. These perceptions are evaluated in the brain and the evaluation is sent to the hypothalamus that sends varying levels of ACTH via the blood to the adrenal cortex. This regulates the production of glucocorticoids by the adrenals which are delivered to the cell nuclei. The glucocorticoid level within the nuclei regulates the translation of genes into proteins. Individuals differ in their rate of translation. As stress levels increase, the number of polymorphs increase while the number of lymphocytes decrease with little change in the total blood count. Because of this, a neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio relates much better than plasma glucocorticoid level to the physiological effects of stress on many factors (Gross and Siegel 1983). The response to a very short term stress begins in about 12 hours, peaks in 20 hours and returns to normal in about 36 hours. A longer stress results in a longer peak response. Vocalizations, behaviors, and productivity are very good evaluations of environmental quality (Stone et al 1984).

A wide variety of stressors can alter the stress response. The same stressor is perceived differently by different individuals in a population. Animals tend to adapt to repeated exposure to the same stressors except one’s place in the social order, relationship to humans, and a disease in progress. For example, laying chickens have reduced egg production in response to heat stress. If chicks are exposed to a short-term elevation of temperature during brooding, after they are over 10 days of age, they tend to be resistant to increases in temperature later in life (Arjona 1983). Exposure to stressors between 1 and 7 days of age results in a wide variety of responses to many factors among individuals later in life. Because of this, newly born or hatched animals should be protected from harsh environmental changes (Gross and Siegel 1980).

Animals have limited resources available for various needs. Allocation is determined genetically. The genetic makeup of individuals within a population varies greatly. For example, if chickens are selectively bred for a high antibody response to an erythrocyte antigen, fewer resources are available for body weight than L antibody line chickens. Weight gain has a low priority for resources. A population of chickens was selectively bred for either a high (H) or low (L) level of antibody response to the same antigen. The possible lines and crosses between the stocks are HH (male-female), HL, LH, or LL. Each of these groups is either most or least resistant to diseases for which the proper defense is antibody. T cell, polymorphs, or monocytes. This suggests that within populations there is a wide variability of resistance to a wide variety of diseases. Responses to genetic factors are influenced by the level of environmental stress. Allocation of resources to defense against the various diseases is controlled by the animal’s perception of its environment. Defense against a wide variety of diseases and environmental stressors is resource-expensive, which leaves fewer resources for productivity (Gross 2002).

If chickens are raised singly in cages there are no social interactions and the P/L ratio of about 0.25 indicates a very low level of stress. Their vocalizations indicate contentment. This results in increased susceptibility to bacterial diseases and external parasites (Hall and Gross 1975). Since the production of digestive enzymes is reduced, their appetite for food is reduced. They eventually die of starvation in the presence of food.

If individuals in flocks of 5 chickens are rotated among a group of cages twice a week there is much difficulty in establishing social orders. Social interactions for dominance are common resulting in lesions particularly on the comb. A high P/L ratio of about 0.55 indicates a high level of social stress. The most dominant chicken has the lowest P/L ratio while the #2 chicken has the highest P/L ratio. Vocalizations indicate anxiety. Growth rate and feed efficiency are reduced because of the diversion of resources to the stress response. Chickens tend to be resistant to bacterial diseases and external parasites with increased susceptibility to viral diseases and a decreased antibody response. Resistance to bacterial disease is very good if the P/L ratio is 0.72. Higher and lower values are less effective (Gross and Siegel 1981).

If individuals are raised in stable flocks of 5, social orders are quickly established. Their vocalizations indicate contentment. A P/L ratio of about 0.4 indicates a stress level that is between that of the previous groups. Genetic tendencies for disease resistance and other factors are easily expressed while growth rate and feed efficiency are high. Individuals need the stimulus of a group. Optimal group size varies among flocks. This medium stress level is the objective of good husbandry and genetic selection (Gross and Siegel 1981).

The adrenal stress response can be blocked by a narrow optimal dose of a variety of chemicals. This increases host defense against a variety of diseases such as tuberculosis, tumors, and viruses. The adrenal stress response can be increased by a narrow optimal dose of glucocorticoids or ACTH. The optimal dose depends on the animal’s P/L ratio. This greatly increases resistance to bacterial diseases. A narrow optimal dose of ascorbic acid results in increased resistance to tuberculosis, tumors, viruses, and bacterial infections resulting in decreased feed efficiency (Gross 1982).

One of the most important factors in improving the mental well-being of animals is their relationship with their human associates. When the relationship is good, expression of genetic potential is increased and resistance to all diseases and stressors are increased. Socialized animals feel confident. They have reduced variation within experimental groups and increased variation between experimental groups. This greatly increases the statistical significance of experimental results. Experimental animals should be given at least 2 weeks to adjust to their social and physical environment. The introduction of new individuals might reduce the stability of adapted groups. Kind human relationships should begin as soon as animals are acquired (Gross 1982).

Large flocks of housed poultry which have good nutrition, protection from weather, predators, and parasites as well as a good relationship with their human associates have very good productivity, feed efficiency, and resistance to stressors. They quickly reallocate resources in response to disease exposure (Gross et al 2002).

How an animal views its social and physical environments and its human associates greatly affects body functions. These factors are very important in our relationships with animals.

References

Robert Ader (ed). 1981. Psychoneuroimmunology, New York: Academic Press.

Marc Bekoff (ed). 2002. The Cognitive Animal, Boston: MIT Press.

Kristin Lee Bell. 2002. Holistic Aromatherapy for Animals, Forres, Scotland: Findhorn Press.

D. K. Belyaev & L. N. Trut. 1975. Some genetic and endocrine effects of selection for domestication in silver foxes, pp. 416-426 in MW Fox (ed). The Wild Canids: Their Systematics, Behavioral Ecology and Evolution, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Thomas Berry. 1999. The Great Work: Our Way into the Future, New York: Bell Tower.

R. W. R. Brambell. 1965. Report of the Technical Committee toEnquire into the Welfare of Animals Kept Under Intensive Livestock Husbandry Systems, (Cmnd. 2836) London: HM Stationery Office.

A. A. Brion and H. Ey. 1964. Psychiatrie Animale, Paris, France: Brouwer.

Charles Darwin. 1920. The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals, New York: Appleton Co.

H. Davis & D. Balfour (eds). 1992. The Inevitable Bond: Examining the Scientist-Animal Interactions, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

V. H. Denenberg. 1967. Stimulation in infancy emotional reactivity and exploratory behavior, pp. 161-190 in D. C. Glass (ed). Neurophysiology and Emotion, New York: The Rockefeller University Press.

Rene’ Descartes. 1970. Philosophical Letters, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

M. C. Diamond, B. Linder & A. Raymond.1967. Extensive cortical depth measurements in neuron size increases in the cortex of environmentally enriched rats. In J. Comp. Neurol. 131: 357-364.

N. H. Dodman & L. Shuster (eds). 1998. Psychopharmacology of Animal Behavior Disorders, Malden, MA.

Larry Dossey. 2001. Healing Beyond the Body: Medicine and the Infinite Reach of the Mind, Boston, MA: Shambala Press.

Michael W. Fox. 1962. Observations on paw raising and sympathy lameness in the dog. In Vet. Rec., 74: 895-896.

Michael W. Fox (ed). 1968. Abnormal Behavior in Animals, Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders Co.

Michael W. Fox. 1971. Integrative Development of Brain and Behavior in the Dog, Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Michael W. Fox. 1972. Understanding Your Dog, New York, NY: Coward, McCann & Geogehan. Reprinted by St. Martin’s Press, New York, NY in 1972.

Michael W. Fox. 1974. Concepts in Ethology: Animal and Human Behavior, Vol. 2, The Wesley W. Spink Lectures in Comparative Medicine, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Michael W. Fox. 1984. Farm Animals: Husbandry, Behavior and Veterinary Practice, Baltimore, MD: University Park Press.

Michael W. Fox. 1986. Laboratory Animal Husbandry: Ethology, Welfare and Experimental Variables, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Michael W. Fox. 1990. The Healing Touch, New York: New Market Press.

Michael W. Fox. 1992. Superpigs and Wondercorn: The Brave New World of Biotechnology and

Where It All May Lead, New York: Lyons and Burford.

Michael W. Fox. 1996. The Boundless Circle: Caring for Creatures and Creation, Wheaton, IL: Quest Books.

Michael W. Fox. 1997. Veterinary Bioethics, pp. 673-678 in A. M. Schoen & S. G. Wynn (eds) Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicine, St. Louis, MO: Mosby.

Michael W. Fox. 1999. Beyond Evolution: The Genetically Altered Future of Plants, Animals, the Earth and Humans, New York: Lyon’s Press.

Michael W. Fox. 2001. Bringing Life to Ethics: Global Bioethics for a Humane Society, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

W. H. Gantt. 1944. Experimental basis for neurotic behavior. In Psychosomatic Medicine Monographs, vol. 3, New York: Woeber.

Joseph P. Garner & Georgia J. Mason. 2002. Evidence for a relationship between cage stereotypies and behavioral disinhibition in laboratory rodents. In Behavioral Brain Research, 136: 83-92.

E. Gellhorn. 1968. Central nervous system tuning and its implications for Neuropsychiatry. In J. Nerv. & Mental Dis., 147: 148-162.

Bernard R. Grad. 1965. Some biological effects of laying-on-of-hands: A review of experiments with animals and plants. In Journal of Amer. Soc. Psychical Res. 59, no. a: 95-127.

D. Griffin. 1977. The Question of Animal Awareness, New York: Rockefeller Press.

W. B. Gross, K. C. Roberts & R. Gogal. 2001. Ascorbic acid as a possible treatment for canine tumors. In Journal of the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association, 20: 35-40.

P. H. Hemsworth & G. J. Coleman. 1998. Human Livestock Interactions: The Stockperson, Productivity and Welfare of Intensively Farmed Animals, CABI Publishing, CAB International.

Debra Horwitz, Daniel Mills & Sarah Heath. 2002. BSAVA Manual of Canine and Feline Behavioral Medicine, Quedgeley, UK: British Small Animal Veterinary Association.

A.H. Katcher & A. M. Beck. 1983. New Perspectives on Our Lives with Companion Animals, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

J. Kratch. 1954. Fright-thyrotoxicosis in the wild rabbit, a model of thyrotropic alarm-Reaction. In Acta Endocrin, 15: 355-367.

D. Marsden. 2002. A new perspective on stereotypic behavior problems in horses. In Vet. Rec.: In Practice, Nov./Dec., 558-569.

G. P. Moberg & J. A. Mench (eds). 2000. The Biology of Animal Stress: Basic Principles and Implications for Animal Welfare, New York: CAB International.

A. B. Lawrence & J. Rushen (eds). 1993. Stereotypic Animal Behavior: Fundamentals and Applications to Welfare, Tucson, AZ: CAB International.

S. Levine & R. F. Mullins, Jr. 1966. Hormone influences on brain organization in infant rats. In Science, 152: 1585-1592.

H. S. Lidell. 1956. Emotional Hazards in Animals and Man, Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas.

Franklin D. McMillan. 1999. Effect of human contact on animal well-being. In JAVMA, 215: 1592-1598. The placebo effect in animals. In JAVMA, 215: 992-999.

Franklin D. McMillan. 2002. Development of a mental wellness program for animals. In JAVMA, 220: 965-972.

Franklin D. McMillan. 2003. A world of hurts–is pain special? In JAVMA, 223: 183-186.

R. M. Nerem, M. J. Levesque & J. F. Cornhill. 1980. Social environment as a factor in diet induced atherosclerosis. In Science, 208: 1475-6.

J. S. J. Odendaal & R. A. Meintjes. 2003. Neurophysiological correlates of affiliative behavior between humans and dogs. In The Veterinary Journal, 165: 296-301.

J. B. Overmeier. 1981. Interference with coping: an animal model. In Acad. Psychol. Bull,, 3: 105-118.

J. Panskeep. 1998. Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions, New York: Oxford University Press.

P. Pavlov. 1928. Lectures on Conditioned Reflexes, W. H. Gantt, trans. New York: International Publishers.

Alfred J. Plechner with Martin Zucker. 2003.

Alfred J. Plechner with Martin Zucker. 2003. Pets at Risk. In From Allergies to Cancer: Remedies for an Unexpected Epidemic, Troutdale, OR: New Sage Press.

Curt Richter. 1954. The effects of domestication and selection on the behavior of the Norway rat. In J. Natl. Cancer Inst., 5: 727-738.

M. R. Rosenzweig, D. Krech, E. L. Bennett & M. C. Diamond. 1962. Effects of environmental complexity and training on brain chemistry and anatomy: A replication and extension. In J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol., 55: 429-437.

J. P. Scott & J. L. Fuller. 1965. Genetics and Social Behavior of the Dog, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

M. F. Seabrook. 1984. The psychological interaction between the stockman and his animals and its influence on performance of pigs. In Vet. Rec., 115: 84-89.

M. E. Seligman. 1975. Helplessness: On Depression, Development and Death, San Francisco: W. H. Freeman and Company.

Rupert Sheldrake. 2000. Dogs That Know When Their Owners Are Coming Home: And Other Unexplained Powers of Animals, New York: Crown Publishing Group.

G. Sheppard & D. S. Mills. 2003. Evaluation of dog-appeasing pheromone as a potential treatment for dogs fearful of fireworks. In Vet. Rec., 152: 432-436.

Rene’ Spitz. 1949. The role of ecological factors in emotional development. Child Develop., 20: 145-155.

B. R. Stockard. 1941. The Genetic and Endocrine Basis for Differences in Form and Behavior, Philadelphia: Wistar Institute Press.

Francoise Welmsfelder. 1990. Boredom and laboratory animal welfare, pp. 243-372. In B. E. Rollin & M. L. Kesel (eds), The Experimental Animal in Biomedical Research, Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press Inc.

Hanno Wurbel. 2001. Ideal homes? Housing effects on rodent brain and behavior. Trends Neurosci., 24: 207-211.